Containing Multitudes: Gregoire Maret Speaks

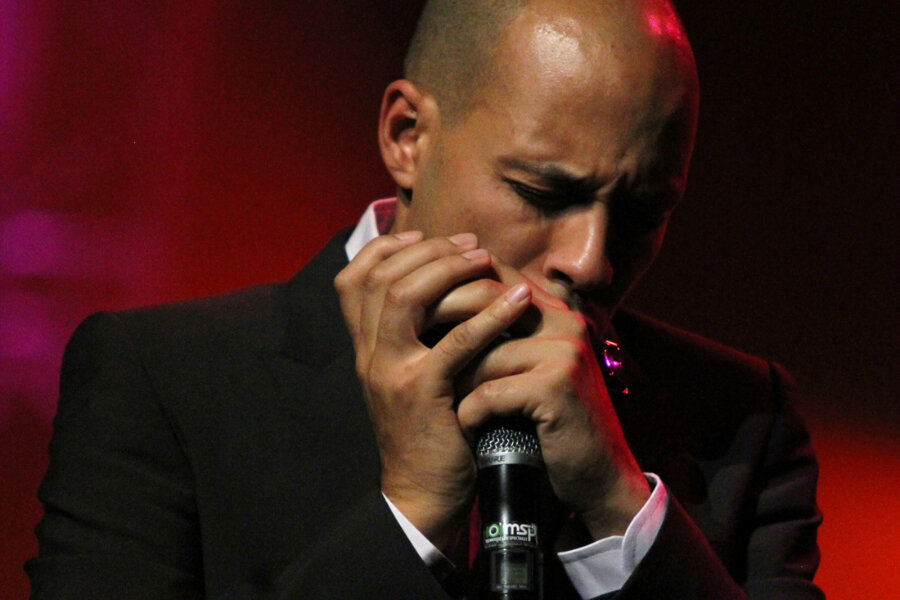

For someone who plays such a small instrument, Gregoire Maret makes music that covers a vast territory. It ranges from groove-based to polyrhythmic to vocal-centric, and what drives the harmonica player and prolific composer to create a body of work characteristically ungoverned by genre, comes down to feeling. “It all starts with the heartbeat,” he says.“When you talk about the pulse and the drumbeat, you talk about the heartbeat. Then when you start talking about any other instrument, it’s basically a voice. I get back to those really, really essential elements [when I’m composing], and then I’ll go with what feels really true and honest to me.”As a young musician growing up in Switzerland, Maret surrounded himself with as much live and recorded music as he could, eventually earning acceptance to the Conservatoire Supérieur de Musique de Genève. After graduating, he traveled to New York to study at the New School, where he began spending quite a bit of his free time with pianist and keyboardist Federico González Peña, who introduced him to the music of composers like Ivan Lins and Milton Nascimento. Through these sessions, Maret found himself instantly attracted to what he considers a music that satisfies the duality of his artistic expression.“I’ve always been attracted to music that felt both simple and sophisticated at the same time. So, with a seemingly quite simple melody, you can have, underneath, a lot of complexity and a lot of elements that can feed the soul. A great example of that is Brazilian music; it’s a huge influence for the way I write music—Brazilian music and Brazilian composers, because I think they mix that really, really well. They sing incredibly simple melodies and, underneath it, if you really listen to the chords and the harmony, it’s quite sophisticated. And then, with a groove that is so beautiful—I don’t have the words to express it. It’s so embracing. Everybody wants to dance. That’s the thing about Brazilian music that really influenced me a lot is the fact that it’s so embracing—it’s so welcoming. You go in a stadium and everybody’s singing the melody—and it doesn’t matter if nobody can sing! It’s just this whole community in which we all embrace each other and are here together. It’s a beautiful thing.”After he began spending time in Brazil, playing, Maret fell even more deeply in love with the music. He studied baião and other rhythms of the north and visited coffee houses and bars in Rio, retracing the hang culture of Jobim and other architects of bossa nova. Touched by the inclusive nature of Brazil’s musical tradition, Maret draws certain parallels between its cross section of cultural influences and that of American music—remaining inspired by both.“When you talk about Brazilian music, you have different cultures that mix, from the Indians to the Black slaves to the Europeans—it’s all mixed, and it created what we know now as Brazilian music, which is an amazing art form. And then here in the U.S., it’s completely different but it’s also those mixes that created, really, what is the American music art form. And when you talk about jazz, you talk about R&B, you talk about anything—it’s really those mixes that made it so special.”While a strong connection to Brazil has had an impact on Maret’s musicianship, what compels him to write is a response to something more intangible. Wanted, his third record as a leader (or co-leader) represents a range of experiences, both outward and inward-looking“I’ll start playing a melody on piano or a couple different chords, and it has to make me feel really special. I have to think, ‘Wow, those chords are so beautiful, so great—I want to write a song with that,’ or ‘There’s something about this melody that feels really special, so I want to come up with some chords.’ And then once I harmonize a melody—it can be endless the way to harmonize a melody. So I’ll try different ways and see which ones makes me feel like—like I get excited every time I play those chords. And once I feel like there’s something really strong going, that’s when I start to be like, ‘Okay, I think I have something here.’ Then I’ll keep on going until I have a song and it’s complete.’”Timeline, to Maret, is arbitrary. He’s more concerned with exploring a piece of original music in a way that guarantees personal satisfaction—even if that exploration spans beyond the time it takes to move from one record to the next.“Sometimes I’ll work on a song for months—for years, reworking it until I feel it’s really finished. And sometimes it’s very quick. There are times when I’ll find a melody and within an hour—a half an hour—I’ll have the entire song written. Then there’s other times where I’ll have just this little bit of a melody that I like, and I take literally years to finish it because I keep finding different chords or different rhythm patterns that I could use with it—all kinds of stuff that I explore until I feel I’m really serving the melody, like I’m really about this melody—this is what the melody’s about. This is the way it should be harmonized and presented rhythmically. Sometimes it takes a long time.”Some artists feel a tremendous pressure to continue recording and releasing once they’ve put out their first record as a solo leader. Since the release of his self-titled album in 2012, however, Maret has remained focused and self-possessed. A musician who’s most comfortable spending five or six hours a day composing at the piano, Maret sought to rearrange his daily routine after the birth of his daughter in 2016, in order to spend time with her. But for the prolific composer, the transition proved to have minimal impact on his recording calendar.“I really want to spend time with her so I’m composing less than I used to, but it’s okay. There will be a time for it again. And before she was born, I’d composed so much music that I have enough material to release at least four or five records. Those songs sometimes still need work; sometimes I won’t be satisfied with them and I just won’t release anything. But I have, right now—not finished quite, but almost ready—three or four records. It’s not just the music; it’s recorded—finished. I just need to put on the final touch. I just keep working all the time on music because I love music so much—and I love so many different styles of music, which is a little tricky sometimes because I have to make a choice.”What Maret has chosen to present this week at The Jazz Gallery reflects two distinct sets of music, both of which have kept him busy crafting and refining for the past few years. The Gospel According to Gregoire Maret (The Gospel) features his original songs, arranged and produced by friend and colleague Shedrick Mitchell, who will be on piano and organ for the performance. The other set of music features songs of Stevie Wonder, completely rearranged “It’s also something I worked on with Shedrick,” says Maret. “You’re not going to outdo Stevie Wonder, so either you do it completely differently, or you don’t do it at all.”This concert marks the first time Maret will present The Gospel strictly as an instrumental performance. Whether alongside a full choir or a featured vocalist, Maret always has included voices in this particular project.“I really wanted to write songs when I started working on this gospel [project]. I didn’t want to write tunes, because before that, that’s what I was focusing on, ‘Okay I’m going to write this big suite—this three-part suite.’ But here, it’s completely different. I wanted to do a song that tells a story in itself, and is just a concise and relatively short statement. And it should speak for itself. So it’s a completely different approach, but that’s really what I wanted to do. And I wanted to see if I was able to do it, because a lot of my favorite artists, that’s what they’ve been doing. And I wanted to work on that and see if I had any ability in that sense.”Maret’s connection to the voice is a powerful one. He seeks out frequent collaborations singers, often arranging his tunes so he may play certain melody lines in unison with them. Over the years, he’s worked with such distinctive vocalists as Cassandra Wilson, Luciana Souza, Dianne Reeves and Jimmy Scott, whom he credits for teaching him how to play a ballad.Before he ever picked up the harmonica, Maret was a singer. But when his voice changed, he found he was no longer able to sing, a loss that proved devastating for the developing artist. “The reason I picked the harmonica is because it was so close to the voice,” he says.“The way I play harmonica is, I play exactly what I hear. So, as crazy as it may sound because of all those crazy intervals or whatever, it is exactly what I’m hearing. If I were to sing, those are the things that I would sing. So it’s really my voice, and there’s a very vocal quality to the harmonica—the instrument itself, but also the way I hear it. So for me, it’s very natural to connect with other vocals, because I consider the harmonica a voice.“On my musical path, I naturally started working a lot with vocalists, from Jimmy Scott to Cassandra Wilson, with whom I’ve worked for over 10 years. I have to give a whole lot of daps to Terri Lyne Carrington because she’s the one who hooked me up with Cassandra—and Herbie Hancock. And that connection with Cassandra Wilson really changed my life. It just put me in another place, and I did really well from that point on. So it was really thanks for Terri Lyne Carrington that it happened, but also I have to thank Cassandra for being generous and taking me in her band for 10 years and allowing me to grow.”Beyond his profound connection to the voice and self-imposed challenge to songwrite, another incentive for writing The Gospel was Maret’s desire to reunite with Mitchell and drummer Marcus Baylor, both old school friends, and both of whom will be featured on the record’s forthcoming release. But as Marcus became increasing busy with his recent GRAMMY-nominations for The Baylor Project, Maret had the good fortune of connecting with Nathaniel Townsley, who will be part of the Gallery performance.“It’s been incredible. To me, he’s one of the greatest drummers—ever. He’s such a beautiful person, too. He’s so supportive and special. So it’s been a blast to play this music with those guys. And then the last member is DJ Ginyard on bass who is like—my brother. I love him, too, to death. He’s a beautiful, beautiful soul and a great musician and he’s very supportive, also. It’s a special unit of people.”When Maret sits down to compose or raises his harmonica to play, what he’s really doing is searching for something he can present truthfully, for better or worse, as a part of his own, singular expression. “I’m always reaching for a place where I feel fulfilled,” he says. “You can say that it’s, in a sense, a bit selfish because before I can really see how people react to it, it’s really about how I feel about it. I have to be proud of it, myself, and feel satisfied.”Gregoire Maret & Inner Voice plays The Jazz Gallery this Saturday, March 24, 2018. The group features Mr. Maret on harmonica, Shedrick Mitchell on piano and Hammond B3, DJ Ginyard on bass, and Nathaniel Townsley on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $25 general admission ($10 for members), $35 reserved cabaret seating ($20 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.

For someone who plays such a small instrument, Gregoire Maret makes music that covers a vast territory. It ranges from groove-based to polyrhythmic to vocal-centric, and what drives the harmonica player and prolific composer to create a body of work characteristically ungoverned by genre, comes down to feeling. “It all starts with the heartbeat,” he says.“When you talk about the pulse and the drumbeat, you talk about the heartbeat. Then when you start talking about any other instrument, it’s basically a voice. I get back to those really, really essential elements [when I’m composing], and then I’ll go with what feels really true and honest to me.”As a young musician growing up in Switzerland, Maret surrounded himself with as much live and recorded music as he could, eventually earning acceptance to the Conservatoire Supérieur de Musique de Genève. After graduating, he traveled to New York to study at the New School, where he began spending quite a bit of his free time with pianist and keyboardist Federico González Peña, who introduced him to the music of composers like Ivan Lins and Milton Nascimento. Through these sessions, Maret found himself instantly attracted to what he considers a music that satisfies the duality of his artistic expression.“I’ve always been attracted to music that felt both simple and sophisticated at the same time. So, with a seemingly quite simple melody, you can have, underneath, a lot of complexity and a lot of elements that can feed the soul. A great example of that is Brazilian music; it’s a huge influence for the way I write music—Brazilian music and Brazilian composers, because I think they mix that really, really well. They sing incredibly simple melodies and, underneath it, if you really listen to the chords and the harmony, it’s quite sophisticated. And then, with a groove that is so beautiful—I don’t have the words to express it. It’s so embracing. Everybody wants to dance. That’s the thing about Brazilian music that really influenced me a lot is the fact that it’s so embracing—it’s so welcoming. You go in a stadium and everybody’s singing the melody—and it doesn’t matter if nobody can sing! It’s just this whole community in which we all embrace each other and are here together. It’s a beautiful thing.”After he began spending time in Brazil, playing, Maret fell even more deeply in love with the music. He studied baião and other rhythms of the north and visited coffee houses and bars in Rio, retracing the hang culture of Jobim and other architects of bossa nova. Touched by the inclusive nature of Brazil’s musical tradition, Maret draws certain parallels between its cross section of cultural influences and that of American music—remaining inspired by both.“When you talk about Brazilian music, you have different cultures that mix, from the Indians to the Black slaves to the Europeans—it’s all mixed, and it created what we know now as Brazilian music, which is an amazing art form. And then here in the U.S., it’s completely different but it’s also those mixes that created, really, what is the American music art form. And when you talk about jazz, you talk about R&B, you talk about anything—it’s really those mixes that made it so special.”While a strong connection to Brazil has had an impact on Maret’s musicianship, what compels him to write is a response to something more intangible. Wanted, his third record as a leader (or co-leader) represents a range of experiences, both outward and inward-looking“I’ll start playing a melody on piano or a couple different chords, and it has to make me feel really special. I have to think, ‘Wow, those chords are so beautiful, so great—I want to write a song with that,’ or ‘There’s something about this melody that feels really special, so I want to come up with some chords.’ And then once I harmonize a melody—it can be endless the way to harmonize a melody. So I’ll try different ways and see which ones makes me feel like—like I get excited every time I play those chords. And once I feel like there’s something really strong going, that’s when I start to be like, ‘Okay, I think I have something here.’ Then I’ll keep on going until I have a song and it’s complete.’”Timeline, to Maret, is arbitrary. He’s more concerned with exploring a piece of original music in a way that guarantees personal satisfaction—even if that exploration spans beyond the time it takes to move from one record to the next.“Sometimes I’ll work on a song for months—for years, reworking it until I feel it’s really finished. And sometimes it’s very quick. There are times when I’ll find a melody and within an hour—a half an hour—I’ll have the entire song written. Then there’s other times where I’ll have just this little bit of a melody that I like, and I take literally years to finish it because I keep finding different chords or different rhythm patterns that I could use with it—all kinds of stuff that I explore until I feel I’m really serving the melody, like I’m really about this melody—this is what the melody’s about. This is the way it should be harmonized and presented rhythmically. Sometimes it takes a long time.”Some artists feel a tremendous pressure to continue recording and releasing once they’ve put out their first record as a solo leader. Since the release of his self-titled album in 2012, however, Maret has remained focused and self-possessed. A musician who’s most comfortable spending five or six hours a day composing at the piano, Maret sought to rearrange his daily routine after the birth of his daughter in 2016, in order to spend time with her. But for the prolific composer, the transition proved to have minimal impact on his recording calendar.“I really want to spend time with her so I’m composing less than I used to, but it’s okay. There will be a time for it again. And before she was born, I’d composed so much music that I have enough material to release at least four or five records. Those songs sometimes still need work; sometimes I won’t be satisfied with them and I just won’t release anything. But I have, right now—not finished quite, but almost ready—three or four records. It’s not just the music; it’s recorded—finished. I just need to put on the final touch. I just keep working all the time on music because I love music so much—and I love so many different styles of music, which is a little tricky sometimes because I have to make a choice.”What Maret has chosen to present this week at The Jazz Gallery reflects two distinct sets of music, both of which have kept him busy crafting and refining for the past few years. The Gospel According to Gregoire Maret (The Gospel) features his original songs, arranged and produced by friend and colleague Shedrick Mitchell, who will be on piano and organ for the performance. The other set of music features songs of Stevie Wonder, completely rearranged “It’s also something I worked on with Shedrick,” says Maret. “You’re not going to outdo Stevie Wonder, so either you do it completely differently, or you don’t do it at all.”This concert marks the first time Maret will present The Gospel strictly as an instrumental performance. Whether alongside a full choir or a featured vocalist, Maret always has included voices in this particular project.“I really wanted to write songs when I started working on this gospel [project]. I didn’t want to write tunes, because before that, that’s what I was focusing on, ‘Okay I’m going to write this big suite—this three-part suite.’ But here, it’s completely different. I wanted to do a song that tells a story in itself, and is just a concise and relatively short statement. And it should speak for itself. So it’s a completely different approach, but that’s really what I wanted to do. And I wanted to see if I was able to do it, because a lot of my favorite artists, that’s what they’ve been doing. And I wanted to work on that and see if I had any ability in that sense.”Maret’s connection to the voice is a powerful one. He seeks out frequent collaborations singers, often arranging his tunes so he may play certain melody lines in unison with them. Over the years, he’s worked with such distinctive vocalists as Cassandra Wilson, Luciana Souza, Dianne Reeves and Jimmy Scott, whom he credits for teaching him how to play a ballad.Before he ever picked up the harmonica, Maret was a singer. But when his voice changed, he found he was no longer able to sing, a loss that proved devastating for the developing artist. “The reason I picked the harmonica is because it was so close to the voice,” he says.“The way I play harmonica is, I play exactly what I hear. So, as crazy as it may sound because of all those crazy intervals or whatever, it is exactly what I’m hearing. If I were to sing, those are the things that I would sing. So it’s really my voice, and there’s a very vocal quality to the harmonica—the instrument itself, but also the way I hear it. So for me, it’s very natural to connect with other vocals, because I consider the harmonica a voice.“On my musical path, I naturally started working a lot with vocalists, from Jimmy Scott to Cassandra Wilson, with whom I’ve worked for over 10 years. I have to give a whole lot of daps to Terri Lyne Carrington because she’s the one who hooked me up with Cassandra—and Herbie Hancock. And that connection with Cassandra Wilson really changed my life. It just put me in another place, and I did really well from that point on. So it was really thanks for Terri Lyne Carrington that it happened, but also I have to thank Cassandra for being generous and taking me in her band for 10 years and allowing me to grow.”Beyond his profound connection to the voice and self-imposed challenge to songwrite, another incentive for writing The Gospel was Maret’s desire to reunite with Mitchell and drummer Marcus Baylor, both old school friends, and both of whom will be featured on the record’s forthcoming release. But as Marcus became increasing busy with his recent GRAMMY-nominations for The Baylor Project, Maret had the good fortune of connecting with Nathaniel Townsley, who will be part of the Gallery performance.“It’s been incredible. To me, he’s one of the greatest drummers—ever. He’s such a beautiful person, too. He’s so supportive and special. So it’s been a blast to play this music with those guys. And then the last member is DJ Ginyard on bass who is like—my brother. I love him, too, to death. He’s a beautiful, beautiful soul and a great musician and he’s very supportive, also. It’s a special unit of people.”When Maret sits down to compose or raises his harmonica to play, what he’s really doing is searching for something he can present truthfully, for better or worse, as a part of his own, singular expression. “I’m always reaching for a place where I feel fulfilled,” he says. “You can say that it’s, in a sense, a bit selfish because before I can really see how people react to it, it’s really about how I feel about it. I have to be proud of it, myself, and feel satisfied.”Gregoire Maret & Inner Voice plays The Jazz Gallery this Saturday, March 24, 2018. The group features Mr. Maret on harmonica, Shedrick Mitchell on piano and Hammond B3, DJ Ginyard on bass, and Nathaniel Townsley on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $25 general admission ($10 for members), $35 reserved cabaret seating ($20 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.