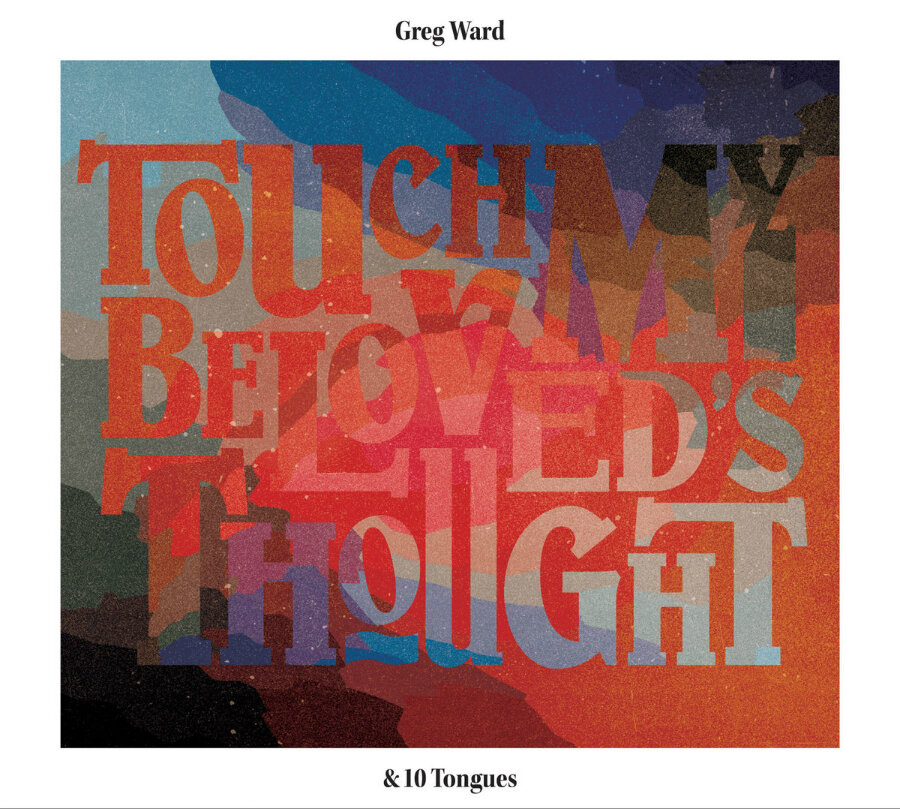

Greg Ward Album Release: Touch My Beloved's Thought

Over the past two decades, alto saxophonist Greg Ward has built himself a strong reputation as a ferocious improviser and thoughtful, multifaceted composer. He's released acclaimed albums with both his Chicago-based group Fitted Shards and his New York trio Phonic Juggernaut. In 2014, Ward was a Jazz Gallery Residency Commission recipient, creating a multimedia work inspired by the sculptor Preston Jackson.Ward's newest project—Touch My Beloved's Thought—is a taut and impassioned reimagining of Charles Mingus's seminal 1963 recording, The Black Saint and The Sinner Lady. Ward was commissioned by The Jazz Institute of Chicago to create the work alongside choreography by Onye Ozuzu; the full production was premiered at Millennium Park in Chicago last year. This Friday, July 8th, marks the release of the project in recorded form on Greenleaf Music, and The Jazz Gallery is proud to welcome Ward and his ensemble 10 Tongues to our stage that evening. We caught up with Ward this week by phone to hear about how he put his own stamp on this Mingus masterpiece, as well as his experiences working with dance.The Jazz Gallery: When was the first time you heard The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady?

Over the past two decades, alto saxophonist Greg Ward has built himself a strong reputation as a ferocious improviser and thoughtful, multifaceted composer. He's released acclaimed albums with both his Chicago-based group Fitted Shards and his New York trio Phonic Juggernaut. In 2014, Ward was a Jazz Gallery Residency Commission recipient, creating a multimedia work inspired by the sculptor Preston Jackson.Ward's newest project—Touch My Beloved's Thought—is a taut and impassioned reimagining of Charles Mingus's seminal 1963 recording, The Black Saint and The Sinner Lady. Ward was commissioned by The Jazz Institute of Chicago to create the work alongside choreography by Onye Ozuzu; the full production was premiered at Millennium Park in Chicago last year. This Friday, July 8th, marks the release of the project in recorded form on Greenleaf Music, and The Jazz Gallery is proud to welcome Ward and his ensemble 10 Tongues to our stage that evening. We caught up with Ward this week by phone to hear about how he put his own stamp on this Mingus masterpiece, as well as his experiences working with dance.The Jazz Gallery: When was the first time you heard The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady?

Greg Ward: It was before we decided to do this project, in October of 2014. Drummer Mike Reed was asked to do it originally and he told me about it, so I decided to check out the record.

TJG: That's interesting, because when I was going through school, Black Saint was one of those records that I felt you had to know.

GW: Yeah [laughs]. I'm someone who likes to listen to something over and over and over and over, because I feel that the better I become as a musician, the more I find in the intricacies of amazing music. That keeps me from listening to a lot of things. I feel very behind myself as a listener!

TJG: What really struck you when you heard the album for the first time?

GW: The orchestration was the first thing that hit me because it was so lush. You have like contrabass trombone, and just a really rich sounding band filling it out. I just noticed immediately that this wasn't your typical head chart kind of piece. There weren't necessarily tunes. It had a narrative, a longer form. That struck me immediately. As the piece unfolded, I was really struck how it featured alto sax. Initially, when I thought that Mike Reed was going to do something with this project and I play with him so much, I was like, "All right! I gotta be in there!"

TJG: When you took over the project, how did you decide on doing your own freer interpretation of the piece, rather than a transcription, or something that hews closer to the original performance?

GW: I felt like some of special moments on the recording were a bit by chance, or via overdubs. Some of the material clearly feels like mistakes. If you listen really closely, you can hear Mingus counting off the band and then stopping them, and then a couple of seconds later hear them start again. I don't think you can really pull that off through a transcription or straight arrangement. So I thought what would be more effective and could really move people was to do something of my own, using some of the themes or just the orchestrational feel as jumping-off points.

TJG: I feel it can be a real psychological challenge to make one's own version of a legendary piece. Did you feel pressure to live up to the original and how did that affect how you worked out the project?

GW: I wanted to do my research because I didn't have the benefit of this being a monumental work in my upbringing in music. I read liner notes, I read different things on the internet, I watched the Mingus documentary [Triumph of the Underdog], just all these things to get inside of what was happening during the recording. It was very important to me that I not mess this up. When I read that this piece is hailed as one of the great orchestrational triumphs in all of jazz, I was like, "Oh no!" It was something that I really took seriously. It was important to me that the people who love that record felt fulfilled and that I could look back on it and say that I did the best I could on it. I hold myself to a high standard in that regard. A lot of people who've seen the live show or heard the record feel the inspiration from The Black Saint and The Sinner Lady, and Mingus's life and work in general. I'm happy about that.

TJG: If Mingus were to hear that someone was doing a project based on his music, do you think he'd prefer this kind of personal approach to the material, rather than doing a transcription of what his band did?

GW: I think so. I think there was this Downbeat Magazine blindfold test that Mingus did. They played something that they think he's gonna like, and he immediately tells them to turn it off. I think it was something kind of modal, and Mingus was saying that they were doing that kind of thing before. He was disappointed that something they were calling "fresh" didn't seem to be doing anything new. So I don't think he would have wanted people to necessarily perform his music in the same vein, or from his perspective. And I really think that's impossible—you don't have the experience of playing and working with him. I hope that he would be happy with me.I look at our lives and I see some similarities in our backgrounds. I'm a multi-racial person and I grew up playing gospel music in the black church. But I have a bit of a different perspective growing up in the '80s, rather than the '30s and '40s.

TJG: To change gears a little bit, what was it like to work with choreographer Onye Ozuzu? Did you have a lot of back on forth while working on the project? Did you change the music to fit her choreography, or vise versa?

GW: Fortunately, we had a decent amount of time to work on the project, so we were able to develop a working method. Outside of really digging into the piece, I started writing out ideas that I thought fit in with the piece. I would play them on the piano and record them and send them to her, and she would dance to excerpts of Black Saint and send me videos. I could see how she moved, how she was creating choreography from the music. As I started creating music that would become part of the work, we kept working in the same way. I would write a little bit and score it in notation software and make recordings using MIDI sounds. I'd send those to her and they would start doing rehearsals. I would watch videos with multiple dancers working through different sections, and we continued in that fashion for about six months. It kept getting more and more refined, so it was a real treat to get to the final product.

TJG: Was this the first time you had written for dance?

GW: No. The first commission I ever received, back in 2005, was from my hometown ballet, the Peoria Ballet. I hadn't done any kind of multimedia collaboration at that point, but it really worked out well. I had a longer period of time to work on it, and I really needed it. It was a forty-minute work with forty dancers and we had a live five-piece band and a great visual artist, Preston Jackson, doing the set design.

TJG: What do you enjoy about working with dance?

GW: It's another way to connect with people. More recently, I went to Bill T. Jones's piece on [Abraham] Lincoln. I was at the premier at the Ravinia Festival in 2009 and to me it was the absolute best collaboration of set design and lighting and music and dance. Everything was so in tune and I was blown away. I called Jones's offices the next day trying to get a job to write music for them! They weren't looking for composers at the time, they told me [laughs]. But I'm just interested in combining different things. Even just in music, you're combining different instruments, creating unique voices. You can have two different instruments playing a line and create a new instrument out of that blend. You can also do that with different mediums. A dancer moving with a melody means something else than just the melody. That's exciting to me, especially as I've gained some skill as a composer over the past eleven years. It's exciting to get to come back and do this kind of work again. The first time I was just trying to figure out everything and I have a little more experience now.

TJG: When you come to the Gallery on Friday, you won't be performing this piece with the dance element. How do you think the experience of the piece will change in this concert setting?

GW: As I listen to the recording, without seeing the dance, I think the piece holds up. I think it has a bit of a different meaning without that element, but I think the music is strong enough. That's the ultimate goal. I think the piece has three lives—it has a life as the music by itself, it has a life as the dance by itself, and it has a life as the full production. Onye Ozuzu has taken the dance to different festivals and presented it without the live band.

TJG: This is a really common thing in the classical world—so much of the most popular orchestral repertoire are ballets performed without the dance.

GW: Yeah. I'm curious about the performance on Friday because they'll be people in New York who haven't seen the dance element. I'm curious to see what their response is.

TJG: How did you go about assembling the band for this project? Were you writing the piece with particular players in mind?

GW: It's like another level of instrumentation, beyond choosing if you want a trumpeter or a saxophone. You want to choose a person with this particular character. With this project, I had an opportunity for me to bring together players who I've worked with for years—Marcus Evans on drums, Jason Roebke, Tim Haldeman, Norman Palm... Tim and Jason and I play in Mike Reed's People, Places, and Things together, and we have such strong rapport. I went to college with Marcus Evans and we used to host the Velvet Lounge jam session. With pianist Dennis Luxion I did a big tour of Africa, and he's such an amazing musician. These are people I've known for almost twenty years. We have all these stories together. It's a real brotherhood. Having that is very important to me. They're all very unique and very expressive as players. To get to write something with them in mind is a real treat.

TJG: We've talked a lot about how you worked on this project as a composer, but I'd like to know a little bit about how you work as a performer in it. In the original Black Saint, alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano plays a really big role. Was he a player you knew much of before this? What have you learned about the piece from his approach?

GW: I wasn't really familiar with his playing before this, but I looked into to find out what his story was. What I hear on the recording is someone who is very flexible. I hear him sounding like Johnny Hodges, I hear him playing these cadenza-like things that evoke Middle Eastern or Flamenco music for me. He's super well-rounded. It was also striking how strongly his voice was written into the orchestration. In some cases, I tried to spread around the work on this project and let other players take on those lead roles, but the alto is lead voice through a lot the situations.

TJG: It wasn't like you were trying to sound like Charlie Mariano, but instead were doing your own version of his leading role.

GW: Right, definitely. I know that I have to be myself, but I know what his role was in the piece. I had to take that into consideration when creating the work. But still, sometimes I wanted to make the piano featured, or the bass trombone featured. I wanted to feature these instruments that I don't get to play with all the time.

TJG: Thanks so much for talking with us. It's really exciting to have this project come to New York!

GW: It couldn't have happened without the support of a lot of people—Greenleaf Records, Dave Douglas and everybody who works there. Mike Reed and Roell Schmidt at Links Hall, and the city of Chicago. It's really one of those perfect storm things. So many people came together to make it happen—it's amazing!

Greg Ward & 10 Tongues celebrate the release of Touch My Beloved's Thought at The Jazz Gallery on Friday, July 8th, 2016. The group features Mr. Ward on alto saxophone, Lucas Pino on tenor saxophone, Keefe Jackson on tenor/baritone saxophones, Russ Johnson on trumpet, Ben LaMar Gay on cornet, Christopher Davis on bass trombone, Willie Applewhite on trombone, Dennis Luxion on piano, Jason Roebke on bass, and Kenneth Salters on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $22 general admission ($12 for members) for each set. FREE for SummerPass holders. Purchase tickets here.