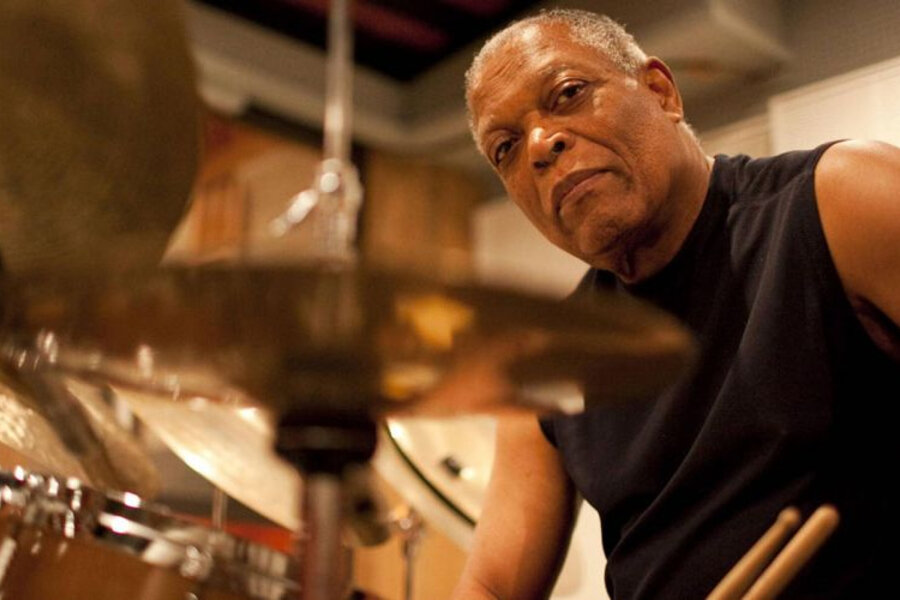

History Lessons: Billy Hart Speaks, Part 1

Many know Billy Hart—Jabali—for his resonant contributions to Herbie Hancock’s sextet during the Mwandishi years. Others know him for his storied associations with Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery, or his early experience performing alongside Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Patti LaBelle. But the new assembly of artists—“the new guard,” to use his words—knows the DC-born drummer, composer and band leader as a towering figure with a sound that continues to evolve the music. He acts as a mentor, showing up for multigenerational protégés; an elder, eagerly inviting younger artists to play next to his fire; and a master of the moment, whose Vanguard sets are known to entrance front rows, back tables, service staff, and management alike.This week, he shares The Jazz Gallery stage with long-running quartet-mates Mark Turner, Ethan Iverson and Ben Street. From his home in Montclair, New Jersey, he spoke with the Gallery for nearly two hours, beginning many thoughtful responses with the same question: “Well…do you want to hear the whole story?” The Jazz Gallery: So many artists in New York, and I imagine elsewhere, consider you a mentor. I’d love to hear about one of your first mentors, Shirley Horn—what playing in her band taught you about the music and about leading a band.

Many know Billy Hart—Jabali—for his resonant contributions to Herbie Hancock’s sextet during the Mwandishi years. Others know him for his storied associations with Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery, or his early experience performing alongside Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Patti LaBelle. But the new assembly of artists—“the new guard,” to use his words—knows the DC-born drummer, composer and band leader as a towering figure with a sound that continues to evolve the music. He acts as a mentor, showing up for multigenerational protégés; an elder, eagerly inviting younger artists to play next to his fire; and a master of the moment, whose Vanguard sets are known to entrance front rows, back tables, service staff, and management alike.This week, he shares The Jazz Gallery stage with long-running quartet-mates Mark Turner, Ethan Iverson and Ben Street. From his home in Montclair, New Jersey, he spoke with the Gallery for nearly two hours, beginning many thoughtful responses with the same question: “Well…do you want to hear the whole story?” The Jazz Gallery: So many artists in New York, and I imagine elsewhere, consider you a mentor. I’d love to hear about one of your first mentors, Shirley Horn—what playing in her band taught you about the music and about leading a band.

Billy Hart: I still play the drums the way she taught me. Every night. How much time have you got?

On first experiences in jazz

I’m from Washington, D.C. My grandmother lived in an apartment across the hall from the best jazz saxophone player in town, at that time. And I would have had no way of knowing that—or even caring because I wasn’t interested in the music on that level, at that time—but my grandmother was late coming home from work. This guy’s wife didn’t like the fact that there was somebody loitering in the hall, so she came out to see what I was doing. When I told her I was waiting for my grandmother, she said, “Well you can’t wait here. You can come in my apartment.” Then her husband came home from work, this guy Roger “Buck” Hill. He was the great tenor saxophone player in town. I had my drumsticks in my back pocket, and he said, “Oh, you’re a drummer.” And he gave me two Charlie Parker records; one was Bird with Strings, “Just Friends”—on the other side was “If I Should Lose You,” and the other one was “Au Privave” and “Star Eyes.” They were two 78 records [laughs]. This is how long ago that was.So I went home and put the records on. Before that, my favorite music was Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. And what’s interesting about that for me, is when I finally got the chance to hang out with Tony Williams, he felt the same way. His favorite group was Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. So anyway, I heard this music. And for some reason, it grabbed me. I can’t even say why because most of my friends were listening to vocal pop music. So I started listening to the records and I ended up putting together a piecemeal drum set, and started playing with the records. Over a period of a couple of years, I guess I got better at it. That’s when I somehow discovered that this music could be heard on the radio—and on the radio they would advertise live performances. So I decided to go to some of these live performances. I didn’t really tell my parents, so that was a problem—because I wasn’t allowed out that late at night. And I was staying out so late, but I still had to get up and go to school in the morning.

Getting Started on the D.C. Scene

So I got to the point where I started asking people to let me sit in. And nobody would let me sit in. They thought it was a joke. They thought it was funny that this little kid was asking to play. And they would say, “Well you can’t sit in now, but maybe we’ll let you sit in in the last set.” But the last set in those days was really, really late. The gigs didn’t even start until 10, so the last set might be 3 o’clock in the morning. I’d have to go on home and deal with my parents, and then go to school. And they still wouldn’t let me play. They wouldn’t let me sit in. So I ended up calling this saxophone player back, and I said, “Man, I been trying to play and they won’t let me play.” So he said, “Well I’ve got this Saturday afternoon gig. You can come down and play with me.” And I know he didn’t really wanna do it. He hadn’t heard me play. He just remembered giving me the records, and that had been two or three years before. He just was being nice. So he let me sit in.

The first tune or two, I was okay—nothing special. But then the last tune, I really messed everything up. I turned the time around. It was a catastrophe. I was really hurt and upset, and I didn’t know anybody, so I was just trying to walk away so I could sit in the corner and lick my wounds. Actually, I was near tears. I really thought I was gonna be better than that. So as I was walking away, somebody grabbed me by my belt buckle and stopped me, and said, “It really wasn’t your fault. It takes three of us to be a rhythm section.” That’s when I realized that Shirley Horn had been playing piano in that session. I thought she was the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen. It was incredible. Whoever the piano player was, which was her, could do all of that [on the bandstand] and then come over and comfort me—anyway, she gave me a lot of confidence from that moment on. I used to save up my lunch money after that time to just go see her play. And she was so great that she would have a gig six nights a week, and it would last for three years.I didn’t realize [long pause]—I thought everybody was that great. I didn’t realize how special she was until I started playing with her. I just knew she had the best drummer in town, which definitely was not me. And after a while, she would ask this guy, “Hey, why don’t you let Billy sit in?” And he would say, “Absolutely not,” [laughs]. And it sort of went on like that until he went out of town to play with somebody. So she came and got me at this rock club. I say rock club, but let’s call it a dance club. It was one of those clubs with sawdust on the floor. And you started at 8 o’clock and went for 40 minutes and then you were off for 20 minutes, til 2. She just came into the club one time and said, “It’s time for you to play with me.” This was another couple years later. And some of the guys I was playing with had been members of James Brown’s band. So my little pop experience had grown to a certain level. But Shirley was a whole other story. And that’s how I joined her band.

Working with Shirley Horn

She never ever told me what to play. But her music was so beautiful to me that I guess I listened a little more intently than I would have with somebody else. And sometimes she would play certain things—ballads and stuff—and it would actually make me cry. I’d have to hold my head down by the snare drum so the audience wouldn’t see me crying [laughs]. That’s the kind of effect she had on me. I guess I always loved ballads, but playing with her, I could really understand what the ballads meant. She was so moving. She taught me who her favorite singers were.Of course she loved Nat King Cole, but then I found out that Ray Charles wanted to sing like Nat King Cole, and Marvin Gaye also wanted to sing like Nat King Cole. I mean really wanted to sing like him. Nat King Cole probably—outside of somebody like, say Paul Roberson—is the most important male vocalist that this country has produced, from my way of looking at it anyway. Frank Sinatra wanted to be Nat King Cole. Oscar Peterson wanted to be Nat King Cole. So she liked Nat King Cole, and she was somehow already acquainted with Sarah Vaughan. And [later on] she got to be really good friends with Carmen McRae. But the one thing that surprised me was she loved the Yellow Brick Road lady—Judy Garland. And I ended up reading her biography or whatever, and she didn’t say it, but a lot of people considered her a jazz singer.But then the other part of Shirley was her piano playing. And as I learned more about the importance of the so-called jazz piano, I thought of her as playing more of somebody like, say Bill Evans. But then you realize Bill Evans comes from Nat King Cole and Duke Ellington. And I guess Nat King Cole in his own way sort of comes from Duke Ellington, too, and that whole legacy of things.Anyway, I remember saying to Shirley, “You must really like Bill Evans.” And she said, “Bill who?” [laughs], and I said, “Bill Evans.” And she said, “No, I don’t know who that is.” And I said that Bill Evans was influenced by those French composers like Debussy and Ravel and those guys, and she said, “Well I do like them. But I like a lot of the Russian composers, also.” And I ended up investigating some of the Russian composers, and I can hear that, too.When she accompanied herself, she would accompany herself like it was the soundtrack of a movie. That had a lot to do with the drama, not only for the audience but for me. You could see this natural environment she could conjure up just by playing the piano behind her vocals. Plus, she could really play the piano. I mean she could really swing. So when we’d play instrumental music, me personally, I always thought of her as a combination of Oscar Peterson and Ahmad Jamal. She didn’t have the facility on the instrument, but who does? Nobody has that facility. But the rhythm patterns—the rhythm section patterns that she had—were so powerful, so clear, that when I moved to New York, I didn’t have much trouble joining in with the New York musicians because of my training with her. She had that vocabulary.

Early Years in New York

I moved to New York, and right away I began to sub for Billy Higgins. Immediately. And with my little bit of pop experience, I began to sub for Billy Cobham. The two guys that helped me when I first came to New York was Billy Higgins and Billy Cobham. [Cobham] still calls me on my birthday.Billy Cobham was a great straight ahead jazz drummer. And the first really great gig that he had was with Horace Silver; Randy Brecker and Benny Maupin were the horn players. Billy Cobham was that. I remember having a conversation with him just before he joined Mahavishnu Orchestra. He was sitting in my car and he’s telling me, “You know I’m going with this guy John McLaughlin.” And I said, “Why would you wanna do a dumb thing like that?” [laughs]. And he said, “Well man, I really think there’s something in jazz rock for me.” And I said, “Well okay Billy, then I won’t have any problem taking on all the gigs you’re gonna leave,” [laughs]. And that’s the way we left it.Next thing I knew, I was going to see him at Carnegie Hall—big, huge venues. And then he was in that band with the Brecker brothers and Abercrombie, Dreams. And all of those guys became stars. If they didn’t become traveling stars, they became television stars. When Cobham left the Mahavishnu Orchestra, he got all these guys in his band and he became a star. He’s still living off of those records he made with those guys. And then they, Michael and Randy Brecker, left his band and became The Brecker Brothers, and their band basically had been Cobham’s band before that. Then Michael got to be a superstar on the saxophone, and there are people to this day who still think Michael Brecker is what I think Coltrane is. That just shows you how big those guys in the Dreams band were.

Billy Hart Quartet performs September 10 for The Jazz Gallery’s virtual Livestream Concert series. The band features Mr. Hart on drums, Mark Turner on saxophone, Ethan Iverson on piano and Ben Street on bass. Sets begin 7:30pm and 9:30pm EDT; tickets are $15/$5 for members to view the performance online. A limited number of tickets (8) at $50 are available for attending the performance in person. Strict social distancing guidelines apply. Click to purchase tickets.