Kenny Wheeler Memorial Concert: Andrew Rathbun Speaks

Canadian-born composer, trumpeter, and flugelhorn player Kenny Wheeler passed away in September at the age of 84 after a period of declining health. Wheeler was and is still revered internationally for his inimitable sound, innovative compositional approach, and collaborations with some of the most influential jazz artists of his time, including Dave Holland and Anthony Braxton.Toronto-born saxophonist and composer Andrew Rathbun has organized a special concert to honor the memory of Wheeler, which will feature a big band performing some of Wheeler's most beloved large ensemble works. Importantly, 100% of the proceeds from this concert will be donated to the Wheeler family to assist with medical costs. We spoke with Andrew by phone to discuss the impact that Wheeler had on him musically and also Wheeler's status as an international jazz icon. Other recent remembrances of Wheeler can be found on Do the Math, including pieces by Darcy James Argue and Ingrid Jensen.This performance received a starred pick from The New York Times.The Jazz Gallery: As a Canadian-born jazz musician, can you speak a bit about how Kenny Wheeler was regarded on the Canadian jazz scene?

Canadian-born composer, trumpeter, and flugelhorn player Kenny Wheeler passed away in September at the age of 84 after a period of declining health. Wheeler was and is still revered internationally for his inimitable sound, innovative compositional approach, and collaborations with some of the most influential jazz artists of his time, including Dave Holland and Anthony Braxton.Toronto-born saxophonist and composer Andrew Rathbun has organized a special concert to honor the memory of Wheeler, which will feature a big band performing some of Wheeler's most beloved large ensemble works. Importantly, 100% of the proceeds from this concert will be donated to the Wheeler family to assist with medical costs. We spoke with Andrew by phone to discuss the impact that Wheeler had on him musically and also Wheeler's status as an international jazz icon. Other recent remembrances of Wheeler can be found on Do the Math, including pieces by Darcy James Argue and Ingrid Jensen.This performance received a starred pick from The New York Times.The Jazz Gallery: As a Canadian-born jazz musician, can you speak a bit about how Kenny Wheeler was regarded on the Canadian jazz scene?

Andrew Rathbun: He was a titan. Everyone was super aware of him and really revered and respected him. He’d come to Toronto every year and do a week at one of the clubs like the Montreal Bistro with Toronto guys like Don Thompson, and he knew those guys really well from Banff [Jazz Workshop].I think that Banff is the biggest connection that people have to Ken. Through Banff he’d just give his music away, and people would take his tunes and play them at sessions. People were playing his music a lot and it became a word of mouth thing because he was the most self-effacing, humble guy; he was humble almost to a fault. He never did anything to promote himself, so whatever fell into his lap was what happened.He made his first record, Gnu High, when he was 40. That’s kind of amazing, right? In the usual trajectory of major jazz artists, they’re not making their first record when they’re 40, but when they’re 22. I think that really belies his stature as an innovator, since it took people a long time to catch up to what he was into and his interesting contributions.

TJG: You also recorded and worked with Kenny a number times; he even performed on your 2002 quintet release, Sculptures. What was that like?

AR: It was like a dream come true. He was one of the people I really wanted to write music for and stand beside and play melodies with, so to listen to him play on my tunes was huge for me. It was still one of my favorite recordings I ever made just because he’s on it. That meant a great deal to me, especially since we recorded it just three weeks after September 11.I actually thought for sure he would cancel because of that, so I told him, “If you don’t want to come, I totally get it,” but he said, “No, I’ll come.” I think a lot of times people used him on projects that he didn’t feel comfortable with, like the music wasn’t necessarily in his strike zone, so I tried to tailor it so he could really sink his teeth into the music. I think he appreciated that.

TJG: When did you first meet him?

AR: I met him at Banff at the early ’90s. It was just … to hear that sound! For him to pick up that flugelhorn and to play with that sound, and to hear that sound in a room—not on a record, but acoustically ... it was just mind-blowing. That’s the one thing about the people I really revere: when you’re in the same room with their sound, with someone like Joe Lovano, you’re standing beside that sound and it’s just so powerful. Ken was the same way.And I remember I begged him for an arranging lesson, and he kind of put me off, day after day after day. Finally, he begrudgingly relented and we started looking through the scores, and he said, “Oh, it’s just some fourths and fifths. That’s all I use.” It was a ridiculous oversimplification of what he did. His music to him was like, “What’s the big deal?” but to everyone else it was like, “This is a big deal!”

TJG: The memorial concert will feature some of Kenny’s iconic large ensemble music from Music for Large and Small Ensembles, like The Sweet Time Suite. Do you remember when you first heard that record?

AR: I first heard the music at Banff, and I distinctly remember that, since he passed, thinking back on all that … it wasn’t until I got the record and sat down and listened to it over and over and over again—especially with that band and the sound of that record, sonically speaking, which is just incredible—that I really realized this is a masterpiece.I put that as one of the best large ensemble records. To me, that’s like the Queens Suite, and it’s on equal footing with any Gil [Evans] and Miles [Davis] record; it’s in the same zone as those masterpieces we all acknowledge. To me, it’s the same: I get the same goose bumps when I listen to Miles Ahead as when I listen to that.

TJG: Any favorite memories of your time with Kenny?

AR: He had a very dry but very funny sense of humor. He was one of those guys who came up with puns and really quick retorts. He had a very self-deprecating sense of humor in an almost dour, almost English way.One time when he was in New York—I think it was when we were doing the record, maybe between the first and second day—we had the band over for dinner. He used to love butter tarts, which is a Canadian dessert, sort of like a personal pecan pie—so my wife made this giant butter tart for dessert. We put it on the table, and Ken hadn’t said a lot during dinner, but he jumped up from the table and grabbed this butter tart, and he looked at everyone: “I don’t know what you all plan on having for dessert, but this is what I plan on having for dessert!” It was so out of character; everybody just fell out.I said this earlier, but Ken was humble and self-effacing, almost to a fault. He had a hard time listening to himself on playbacks, and he’d sort of get frustrated with his own playing, which I found hilarious because anytime he played something, it just sounded like the most beautiful thing—like the most perfect thing you could have played at that very moment.What it sort of taught me is that he was always still looking for some different stuff to play. He was still trying to improvise and trying to push himself to see if he could make a harmonic connection or a rhythmic connection that was even stronger than the one he’d been making. He couldn’t listen to a lot of his own records, to which I thought, “How could you not listen to Angel Song for days on end?"They’re just perfect records; they’re just brilliant. That’s another thing I admired about him: his recordings seem so well crafted in terms of the order and how they’re arranged. It’s never just about, “Here’s a melody and we blow on it and we’re done.”

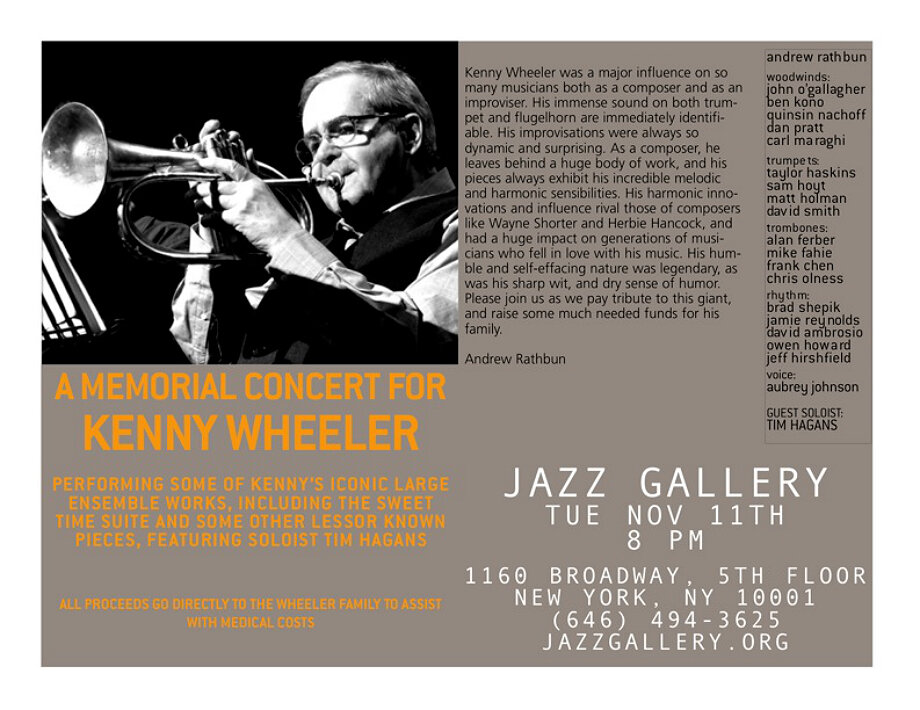

Andrew Rathbun presents a Memorial Concert for Kenny Wheeler on Tuesday, November 11th, 2014, at The Jazz Gallery. The performance will feature a large ensemble with John O’Gallagher, Ben Kono, Quinsin Nachoff, Dan Pratt, and Carl Maraghi on woodwinds; Taylor Haskins, Sam Hoyt, Matt Holman, and David Smith on trumpets; Alan Ferber, Mike Fahie, Frank Chen, and Chris Olness on trombones; Brad Shepik on guitar; Jamie Reynolds on piano; David Ambrosio on bass; Owen Howard and Jeff Hirshfield on drums; Aubrey Johnson on voice; and special guest soloist Tim Hagans. This performance will have one set only at 8 p.m., and tickets are $20.00 for all. 100% of the proceeds will be donated to the Wheeler family to assist with medical costs. Purchase tickets here.