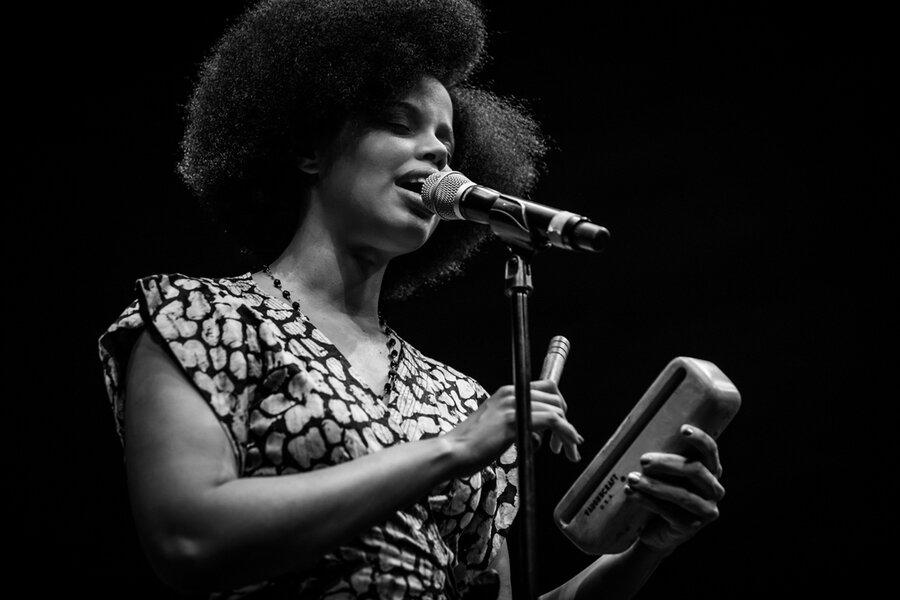

One Source, Many Voices: Melvis Santa Speaks

Multi-disciplinary artist Melvis Santa regards the act of creating music with other people as compelling as the music itself. For the past couple years, the GRAMMY-nominated singer, dancer, percussionist and composer out of Cuba has led different iterations of her acclaimed collective Ashedí—meaning Invitation—across New York City’s vital scenes. This week, she returns to The Jazz Gallery as part of the Jazz Cubano series, in celebration of the venue’s 25th anniversary.Allowing certain secular and spiritual elements to inform her music, Santa and her fellow artists explore new interpretations of rhythmic and melodic ideas from the Yoruba tradition and other styles that trace back to the same source. She discusses mysteries of the drum, the tonal characteristic of Yoruba language and the enduring legacy of the The Jazz Gallery.The Jazz Gallery: Talk to me, if you would, about the sacred connection between percussion and the voice or vocal expression.

Multi-disciplinary artist Melvis Santa regards the act of creating music with other people as compelling as the music itself. For the past couple years, the GRAMMY-nominated singer, dancer, percussionist and composer out of Cuba has led different iterations of her acclaimed collective Ashedí—meaning Invitation—across New York City’s vital scenes. This week, she returns to The Jazz Gallery as part of the Jazz Cubano series, in celebration of the venue’s 25th anniversary.Allowing certain secular and spiritual elements to inform her music, Santa and her fellow artists explore new interpretations of rhythmic and melodic ideas from the Yoruba tradition and other styles that trace back to the same source. She discusses mysteries of the drum, the tonal characteristic of Yoruba language and the enduring legacy of the The Jazz Gallery.The Jazz Gallery: Talk to me, if you would, about the sacred connection between percussion and the voice or vocal expression.

Melvis Santa: The voice in the Afro-Cuban tradition is one of the main elements. It’s definitely sacred because of not only the voice, literally, of the singer but the voice that speaks through the instruments as a spirit, I would say. It’s really important in the religious context, and culturally as well because we inherited that from the African traditions. In oral tradition there is the “culture bearer,” who is someone who has knowledge—deep knowledge—and is the carrier of all those traditions. So either it is the storytellers, or the Babaaláwo, or high priestess Iyalosha, or a mother—all those are people who use their voice as a vessel for knowledge and for tradition.And the sound, specifically in the Yoruba tradition because it’s a tonal language, is very important—tone makes all the differences. In my case, as a singer, I do want to keep having that other perspective to the voice—not only as someone that is just in front of a band expressing feeling spontaneously through the music, but also acknowledging certain responsibility with the legacy I come from. That’s how I see it. It’s a cultural responsibility. We’re transmitting not only sounds but I have a stance with my voice as a communicator. For example, in Lukumí ceremonies we have the akpwon, which is the singer who carries the knowledge to speak directly to the orishas. In order to be an akpwon, you must acquire that knowledge. So that’s my approach, as well.

TJG: We consider the oral tradition all the time when talking about Black American music.

MS: It all comes from Africa.

TJG: It’s illuminating to hear how it’s—almost literally—handed down in the Yoruba tradition.

MS: Yes.

TJG: Why is being a percussionist also important to you in connecting the literal, figurative—or spiritual—vocal tradition?

MS: The instruments are sacred as well, especially in percussion. They are homes for spirits that live inside the drum. It could be interpreted as the sound that you master or the people that work in developing the sound—and not only the sound but the language of the drum—their mission is to find that voice so they can understand and unveil the messages. So in order to have that level of perception, you really have to have a sophisticated sense of development. You have to put all of your senses toward that development. It’s a combination of knowledge, of tradition and of personal investment from inside and outside. The instruments also have their own voice, their own sound. It’s a communication between the instrument, the person that plays and the external elements—like nature, for example.

TJG: How have all these different levels of communicating influenced your style as a composer?

MS: I think it definitely affects my perception of “why.” Why did I choose music? Because I know the cultural context where I come from. And when I say “know,” it’s in the sense that I’ve been raised in a context where music is not something that is far from you. It’s something that you grew into, and there is always a purpose behind music. So having that inspired my development as a human being, as a musician. I think that definitely [offers] a different kind of perception when it comes to me making my music.I feel that I have to say something beyond the musical discourse. I have to be consequent with my spirituality, with my traditions, with my perception. There are elements that somehow allow you to connect your perception to your musical taste or your musical language. For me, being more specific, I find a lot of inspiration in nature—in the elements, the different forces that are beyond just the human being. I see it as a general, bigger combination of elements that we are part of. So I compose from a place that definitely is being grateful, being happy, being sad but at the same time aware that we are not the only ones in this world. I won’t say surrender, but when you open your mind and your senses to all that other existence surrounding you, a lot of things just flow.

TJG: So for you, the best place to begin is inside the natural world.

MS: I think that’s a very good start point. At least for me, it’s an endless source of inspiration.

TJG: You’ve been talking a lot about perception. Since you started Ashedí, you’ve had many different iterations of that band—many different artists who have been part of the project. Do you notice perceptions shifting in terms of what you’ve set out to explore, depending on personnel?

MS: Actually it has to do with the concept of Ashedí, or what I would like Ashedí to be. For me, Ashedí is a conceptual ensemble that doesn’t necessarily fit one format. Ashedí means “invitation” in a metaphorical way. In ceremonial context, Ashedí has a different meaning; it’s a step in the ceremony where you formally bring other people who are also initiated to collaborate together—it’s like an official call to work together. So I’m taking that concept of acknowledging that it’s not only me or not only about me, and calling other people that I know have the same passion as me, and then I’m inviting them into my music, so my music can grow because it’s not only mine anymore. That’s why, with that concept in mind, I realized that Ashedí doesn’t necessarily have to fit one format or sound.Actually, this is what Cuban music is; Cuba is a melting pot of so many styles, cultures, so many influences. Only from Africa we have diverse ethnic groups: Yoruba, which in Cuba is called Lukumí, we also have Bantu, Ekpe—in Cuba transformed to Abakua—Arara, all different from different geographies in Africa. All are different—completely different. I think that the fact that Cuba is an island, plus other conditions in the socio-political aspects, permitted that, even today, those traditions coexist in present society, although readapted in all levels. For me, growing up in that multicultural context taught me to embrace diversity as a harmonic way of living. You learn to find a space for everybody, because everybody is important and definitely have something unique to say. That said, it doesn’t make any sense to me making everything “one thing” because then, you’d be missing so much.Ashedí is the concept of inviting people who share my passion, or something that I think can grow. So the music is a pretext. It could be Rumba music—but a Rumba is a community celebration of life. You connect to it and you share. You speak your truth through Rumba. Also with Ashedí, I like to work a more “Latin jazz” side of me, where I explore my [identity] as a composer in a more intellectual way, let’s say. Although [the style] is more technical musically speaking, it all comes from the same place inside. I enjoy getting together with artists and musicians depending on the style that I wanna [explore], but it all departs from that same family value I was raised in, respecting and embracing diversity.

TJG: In talking about Ashedí, you’re talking about similar but distinct sounds coming from one source.

MS: Mmhm.

TJG: How do you see polyrhythms and syncopation—these varied rhythmic elements you explore—how do they help you tell the story of your ancestors?

MS: Yeah that’s everything. For me, that’s everything. Polyrhythms and syncopation makes all the difference. That’s the main element in Cuban music and, of course, inherited from Africa. So when we say “Cuban,” “Afro” is implicit because in Cuba, it’s almost everything together. But I also like to mark the specific influence African people brought to Cuban music because the rhythm really makes it unique. And polyrhythm and syncopation definitely has, I don’t know, 90 percent or 95—99 percent?—of it [laughs].I can offer a technical example: the clave. Everybody talks about the clave as one thing. In a global perception, it is just one thing. But when you go to the roots of it, we don’t see it as one pattern. You can have the same five beats, and you change the tempo, and it calls for two different styles: one religious, one secular. Not even changing the pattern, just changing the tempo already makes a difference. So that’s what I mean. There’s so much richness, so many details that identify the different cultures within one culture. That’s amazing for me.

TJG: In an earlier response, you mentioned Yoruba is a tonal tradition.

MS: Yes.

TJG: From your perspective, does the tonality of the language have an impact on the harmonic roots of the tradition you’re tugging at with Ashedí?

MS: What I meant to say is that the Yoruba original language is a tonal language. They use different intonation when they speak. When that was brought to Cuba, many Africans—especially the people from Nigeria and Benin that were from the Yoruba ethnic [group]—they had their descendants there. And they were forced to speak Spanish because of the Spanish people that brought them. So the original Yoruba started to get lost until it disappeared. It just was kept by the people that practiced the tradition because they learned the chants and kept the chants in that language. But, inevitably, the original tonality that comes with the language was lost because the Spanish, the Castellano doesn’t have that characteristic. So I think, out of respect for the Yoruba language, they just call it Lukumí, a different name, because it’s not Yoruba. It comes from Yoruba, but it’s not Yoruba. Yoruba is Yoruba and Lukumí is Lukumí.That said, many details were lost. And the harmonic world of that music changed. I don’t know if it’s the right word to say devolve; I will just say change or permute. But it kept the idea of voices and drums. So originally, that music doesn’t really have a “harmony.” It’s very subjective. It’s just voice—melody—and then different tones: the low, the medium and the high. And there has to be a perfect harmony between them, but it’s not something that you really can put in books. It changes with the tone of the drums, and the drums have certain treatment with the sun and the skin that you use. So it’s another approach to harmony, let’s say. It’s like a life harmony.

TJG: What’s been most rewarding to you about these performances you’ve had at The Jazz Gallery in celebration of its 25th anniversary?

MS: I’m really excited and every humbled to be celebrating one more year of the Gallery supporting young musicians, and musicians who have dedicated so many years of their life to jazz. I love jazz. I don’t consider myself a jazz musician, but I do love jazz. I hang with jazz musicians and I see 100 percent the connection with the music that I do and the traditions. And even though the experiences have been specific to each culture, there are common characteristics that are ancestral that come from a very, very long time [ago] that make us coincide at some point, on some level. It’s a sensorial or perception level that I think is beautiful.So The Jazz Gallery is a space that facilitates this kind of collaboration—this exchange. On this occasion, I will be part of the Jazz Cubano series that is curated. In my case, I’m bringing EJ Strickland on the drums. I’m really excited about it because we get to speak about syncopation and perceptions of rhythm, and music in general—sound. And that’s what I think it’s about. I look forward to connecting with people who have different approaches to music but, at the same, time we have something common. And jazz is definitely a genre that allows that kind of exploration.

Melvis Santa’s Ashedí performs this Saturday, March 14, 2020 as part of The Jazz Gallery’s Jazz Cubano series. The band features Ms. Santa on vocals and hand percussion, Ahmed Alom on piano, Carlos Mena on bass and EJ Strickland on drums. Sets are 7:30 and 9:30 p.m. $25/$15 for members; reserved table seating, $35/$25 for members. Purchase tickets here.