People want music: Ulysses Owens Speaks

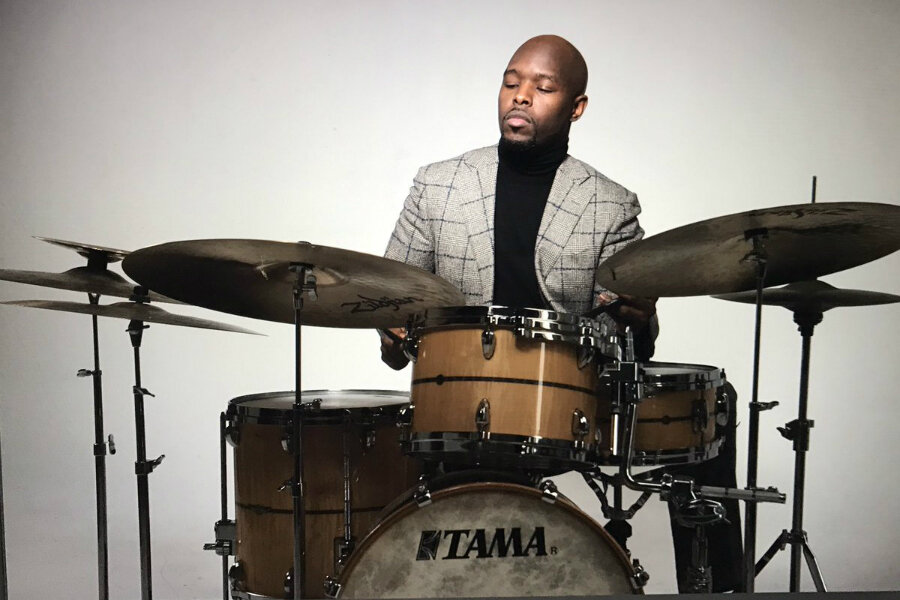

Ulysses Owens Jr. is indisputably one of the most sought-after drummers and producers of his generation. Longtime sideman for Christian McBride and Kurt Elling, Owens breathes air and life into the drums, with crisp, decisive strokes. All the while, he works to cultivate a passion for art in disadvantaged communities. Alongside his organization, Don’t Miss A Beat, Owens often teaches as he tours. His online presence juxtaposes the expected on-stage action shots with candid stills from workshops with wide-eyed students of all ages, from Japan to Jacksonville.

In typical jazz style, Owens continues to step forward as a bandleader as well, expanding his identity as an educator and sideman. “You have to keep reimagining yourself,” he explains as we speak on the phone. In August, Ulysses released his latest album as a leader, Falling Forward (Spice of Life Records). The recording features his newest trio, simply dubbed Three, which features the steadfast Reuben Rogers on bass, and the shimmering vibraphone work of Joel Ross.

To kick off the 2017-2018 season at The Jazz Gallery on September 7th, Owens brings Three to the stage, and in his words, it won’t just be “the album on a silver platter.” They intend to dive deep and explore live nuances of the trio. In our interview with Owens, we strove for the same. Chatting on the phone this week, we considered the personal nature of writing in prose, the relationship between artistry and personal growth, and the specific problems of getting professional musicians invested in minority communities.

-- -- -- -- --

The Jazz Gallery: You released the new CD at Dizzy’s this past month, featuring Vuyo Sotashe. You’ve discussed your collaboration with Joel and Reuben, but tell me a little about Vuyo, who was also on the bill for the release.

Ulysses Owens Jr.: For an initial release, I think it’s special for an audience to experience as much as the album in its initial iteration as possible. That’s why I wanted Vuyo to be involved. He’s an instrument, an instrumentalist through the voice. I love his timbre, his tone. Vuyo’s a star in the making. And one of the kindest people you’ll ever meet. A class act. In his generation, there’s not a lot of people like that. So for Dizzy’s I was thinking, “Here’s the first time New York is gonna hear this music: I want it to be in its original context.”

TJG: Tell me a bit about “Yakhal' Inkomo” track 8 on the album. It really stands out, stylistically, from the rest.

UO: With Vuyo, I put him on the spot in the studio. I knew I wanted him to do two things on the record. So after we recorded what we’d initially planned, I said, “Let’s do something African. Let’s experiment. Roll the tape.” He was so humble, but we dove in. Essentially, the first take is what’s on the album. We did a second version, and when you hear the talking on the track, it’s Vuyo explaining to me what that song is all about between takes. It was this beautiful magic with political relevance too. It’s a song written thirty years ago about Apartheid, and here we are today facing some of the same stuff. I knew I had to put it on the album, it was destiny.

TJG: Did you recreate the tune live?

UO: We did it at Dizzy’s, yeah. In typical Vuyo fashion, he mesmerized the audience. People were crying at the first sound of his voice. And yet he doesn’t take over the ensemble. People heard what he had to say, but it blended with the spirit of the show, and people wanted to hear the trio. He simply emerged as this fourth voice that people really enjoyed. We could highlight our synergy as a trio, while also having Vuyo be a full presence on stage.

TJG: In an interview with 90.1 in Rochester, you said, “As an artist you have to keep reimagining yourself.” Why is it important to reimagine yourself, and how do you keep your integrity in the process of being flexible?

UO: You have to keep reimagining yourself. Evolution is growth, right? You can’t try to do things the same way you did them the day before. It would be impossible. Change is the only constant in this world. And what you experience day-to-day must become who you are as a musician. In today’s industry, we don’t release as much music as they used to release. If you go look at the catalog of anyone before the 1990s, or certainly the 80s, people were putting out two or three records a year. You could see the evolution of an artist through their catalog. Look at Trane, Joe Henderson, Ella, whoever. They were releasing tons of records. You could hear how Ella sounded early on, and who she became at the end of her career when her voice changed. Our generation, we’re so into “the perfect album,” we wanna win a Grammy on day one. We want fame around one project, so we take two years to release it. The result is that you don’t see the evolution. Every day, we wake up and there’s something new about us.

TJG: That’s so interesting. You always hear people talking about how oversaturated the music scene has become. Spotify has 30 million songs or whatnot, and you’ll never be able to listen to everything that’s currently being recorded. It’s nice to hear someone place value on regularly producing music simply as a reflection of personal growth.

UO: That’s the thing, man. People want new music. Why do you think music is more accessible now? Social media is giving artist like us a whole new life. People want to know what you do outside of your practice, because it informs the way they listen. Let’s take an artist like Solange. I have all her records. After two or three records, she teamed up with a great group of producers. She had evolved as a person. She fell in love. She was into fashion, art. She got married. She traveled the world. And then, she produced A Seat At The Table. It’s amazing. And she would have not been able to release it if not for her personal evolution. Being an artist is about documenting your growth as a human. And people people want it. If Solange put out another album today, people would be downloading it and talking about it. If she put out another album eight months later, people would be talking about that too.

TJG: Speaking of personal growth, you published a blog post around the release date of Falling Forward, in which you address your younger self. You discuss your relationship at the time, your business, your mother and sister. Was it difficult getting these thoughts on paper, and how do they relate to the release of your new record?

UO: It’s fascinating that you’re correlating the two, because they have nothing to do with each other in my mind. I love that. Writing is a new muscle for me. And one of the beauties of getting older is that you don’t care as much about people’s opinions of what you want to do. I’ve been in New York for sixteen years. I don’t have anything to prove to anybody but myself. With that said, writing has become this new way of speaking, in a way that I can’t speak through my music. I started the blog about a year ago, and I’ve been trying to get better and better. Right before I wrote Letter To A Prince, I got a new editor. She’s amazing. She ripped me to shreds. “You’re a really talented writer, but you’re hiding,” she said. “Stop hiding behind your words.” I was telling myself, “Okay Ulysses, you’re a drummer, you’re an artist. You have a career out there, so you can’t say too much.” Her response was “Either write who you are and be real, or don’t do it at all.” Letter To A Prince basically tumbled out of that: I was done hiding, and I wanted to write something sincere. People loved it. But the fact that it was released around the same time as the new album, I didn’t really look at it like that.

TJG: Props to your editor for giving it to you straight, and good for you for listening to her! Was it hard taking her advice?

UO: Oh heck yeah. It was a little bit embarrassing to be called out. But it’s exciting to me that people are checking out the blog. I have a bunch of heartfelt things coming up, and I think they’re gonna resonate with people. I’m no Malcolm Gladwell or Ta-Nehisi Coates. There are plenty of other writers who are way more experienced than me. But the only thing you can bring to writing is your authentic voice. So, she’s got me writing better [laughs].

TJG: In that same interview with 90.1 in Rochester, you were asked how to get more more African Americans involved in making music. Your answer was so insightful, centering around getting young people in involved with making music and re-introducing them to creating live art. What do you think is the biggest challenge in making this a reality? I know you also have your organization in Jacksonville, which just got a nice grant from the Community Foundation for Northeast Florida, congratulations!

UO: Whew! You did your research, man! [Laughs]. It’s about access, and I live it every day. The beauty of my life is that I see all sides. Many of my friends, and they’re terrific people, live in Europe or LA – they wake up, they write music, go to shows, tour the world. That’s great, but it’s an insulated world. I live that world; I just got off a plane from a tour in Japan. But then, I live in the other world too. I go to Florida, put myself in the inner city, sit at a community center, and everyone’s walking in off the street. Homeless people, parents who can’t feed their kids, I see all of that, every facet.

To your question, access is key. When you go to an affluent community, they have access. They have systems set up to allow their child to be exposed. One of my closest friends is a Jewish attorney who lives in LA. You see the two of us walking down the street and you’d think, how could those guys be hanging out together? [laughs]. As he’s been raising his kids, from day one, he had a big beautiful Yamaha grand piano in the home. He takes them to the synagogue, where they hear these beautiful prayers being sung. Then, he takes them to my shows. We go to art festivals, museums. Before his girls are eighteen, they will have literally traveled the world through art. That usually doesn’t happen in an African American or minority community. It just doesn’t happen. These kids in the projects, trying to survive, some of these communities don’t even have a grocery store within five miles, so you know there’s no place for them to hear live music. You have babies raising babies. Single parents raising multiple kids. They may get some art at school, but now they’re taking stuff out of the schools too. Or, they’re handed an iPad or cell phone, and you know the kind of crap that’s on there. Man, I think we can talk about “How can we bring art to the next generation,” but first we have to know where the next generation exists. You go to the average eight year old and ask them “Hey, what’s a drum set,” they’ll look at you and go “What do you mean?” They don’t hear it on the radio. We’re surrounded by synthetic sounds. So we have to start introducing it to them in a very natural way.

TJG: So for a professional musician, living the fast life in New York or elsewhere, maybe they don’t have the time, or don’t know the best way to start giving back, what kind of advice would you have for your peers who want to be more community minded and give back?

UO: If you’re a professional musician, you had someone, at some point, take you somewhere, or show you something, or come to your school. So, go to an elementary school. Go to a community center. It’s not that hard. We’re so caught up in our own lives that we don’t see the issue. And if we don’t do this, we won’t have an audience very soon. In twenty years, when the children of today are our young adult audience, they won’t care about what we’re doing, because they just won’t know. So today, not tomorrow, plant some seeds. Give some of yourself away. Once a month, stop at a high school and just talk. Pop music will always have an audience, because it can work in tandem with the social media and mass markets, and will always find a way to be relevant to youth. But with jazz, classical, ballet, even painting and visual art, you have to be shown its value. We live on the outskirts, outside the mainstream. If we don’t cultivate a young audience, there will be no audience. It’s urgent.

TJG: It’ll be fascinating to see what people write about this era, fifty years from now.

UO: We’re in the process of either losing what’s special about us, or getting ready to create a new way of being, which could be great. But I feel like we’re losing something. As much as we’ve gained from technology, we’re losing a lot. I’m interested to see how things unfold. But by then we’ll both be sitting there on the sidelines, watching.

Ulysses Owens, Jr. plays The Jazz Gallery on Thursday, September 7th, 2017. The group features Mr. Owens on drums, Reuben Rogers on bass, and Joel Ross on vibraphone. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $15 general admission (FREE for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.