Raga and Maqam: Amir ElSaffar Speaks

Amir ElSaffar is a performer and composer whose music exists at the crux of ancient and modern traditions. An innovator on trumpet, ElSaffar also plays santur and sings in the traditional Maqam style. His compositions have been commissioned by institutions across the globe, and he has received awards from the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award to the US Artist Fellowship. With his Rivers of Sound Orchestra, he recently released a new album Not Two on New Amsterdam Records to great acclaim. ElSaffar is also the artistic director of Alwan for the Arts, a nonprofit arts & culture organization that showcases cultural and artistic diversity from across the Arab world and South Asia.

For this upcoming show at The Jazz Gallery, ElSaffar will be teaming up with the Brooklyn Raga Massive. Brooklyn Raga Massive was founded in 2012 to bring classical Indian music to a new audience and update the music to match the fast pace and collaborative lifestyle of New York. We spoke at length with ElSaffar about the intricate differences between Maqam and Raga, and the fascinating ways in which they intersect with the world of jazz in New York and beyond.

The Jazz Gallery: For our readers who may not be familiar, what exactly is Maqam, and how does it differ from Raga?

Amir ElSaffar: Maqam is a modal system that are used in the music of the Middle East, North Africa, the Arab world, Turkey, parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Iran, Uzbekistan, all the way to Western China. It’s a system that has many variations, but it’s consistent throughout a large part of the world. Raga and Maqam developed independently of one another, and there’s no overlap, per se. There are even musicians who play Persian, Maqam-based music, as well as Raga, but they don’t necessarily mix the two. Somehow, Raga and Maqam are distinct musical languages. There’s a kind of cross-pollination in North India, with some Hindustani music that was affected by Maqam, and vice-versa with Raga in Persian music, but both are highly distinct.

TJG: Your personal training and immersion has its foundation in Iraqi Maqam. What differentiates Maqam in Iraq from traditions across North Africa, the Near East, Central Asia, and so on?

AE: Iraqi Maqam is one style, one genre, one form within the Maqam tradition. In Iraq, the word “maqam” actually means “a composition,” so by extrapolating on a mode and taking it through all its possibilities, all of the extensions of that mode, in Iraq the Maqams become crystalized as compositions, as forms, that are meant to be performed in somewhat the same manner each time. One can make certain choices within that form, but they become much more specific.

TJG: So it’s a traditional practice, but through that practice it has crystalized into a repeatable form?

AE: Yes. So you have a group of seven notes: It’s not a scale, really, it’s a collection of pitches, each exerting a gravity on the next. Those relationships are powerful. They can be microtonal as well: The E can be half-flat, the F can be half-sharp, there are many gradations of pitch on a continuum. In Raga, you also don’t rest on microtonal pitches as much. There are a lot of glissandi in Hindustani and Carnatic music, but you don’t stop on the microtonal notes between pitches, whereas in Maqam music in general, those pitches have their own characteristic sovereignty.

TJG: How did your relationship with Brooklyn Raga Massive begin, and what kind of material have you been assembling?

AE: We’ve found that there are modes shared between Raga and Maqam, so that was an easy starting point. But the treatment of those modes, how the ornamentation works, which notes get emphasized and which notes get passed over, there’s a lot of subtlety there. The fine tuning is different too. We begin with a Hindustani, Persian, Iraqi, or similar composition, and start assembling the forms. We intersperse improvisation and musical dialogue as well. Maybe we have two people improvising off of each other, with each other.

TJG: Has there been some butting of heads in terms of struggling to find compatibility with the traditional material? Do Maqam and Raga not easily integrate?

AE: I wouldn’t say “butting of heads” because our collaboration has been so respectful. There are certain tuning problems where, for example, one of the Maqams has a very clear second degree that’s A-half-flat. G is the tonic, and the next note is really between A and Ab. The Indian musicians can play that sound very convincingly, but the sitar has these sympathetic strings, so the question is, does the sitar need to be retuned? If that A-half-flat is going against an A natural on sympathetic strings, it deadens the vibration of the instrument, or can cause unwanted sounds. You can retune the strings, but you end up with other issues around the acoustics of the whole instrument. That’s a challenge.

The Raga tuning systems also have challenges, wherein there’s always sustained drone, the shruti, with these resonant pitches. That’s a challenge with Maqam sometimes. There are sometimes Carnatic melodies that have twelve measures, maybe fewer, but the ornaments are so characteristic, and some of these instruments aren’t designed to play fast glissandi in the way a violin can. So, there are some challenges. Ultimately, we aren’t approaching this as “tradition meets tradition,” but rather as musicians meeting, having a musical conversation, an exploration, and in the moment just dealing with the sound, rather than saying “Where did this come from” or “What tradition does this belong to?”

TJG: How does that conversation, this shared arranging of traditional elements, set the stage for you as an improviser?

AE: When you play a composition, it tunes your ear, tunes the instrument, tunes the environment. You’re going to improvise in some way that relates to it. It’s the same way that jazz improvisers may recall the melody of a tune when they’re playing over changes. You’re improvising, yet staying within the feeling of that melody. Thelonious Monk is a great example. Throughout a given improvisation, he’s still recalling the shape and the motifs of the head. So somehow, when we’re improvising on a Hindustani four-measure or eight-measure melody together, the improvisation will probably be affected by that.

TJG: We interviewed Abhik Mukherjee for a previous Brooklyn Raga Massive concert, and we discussed how one of the great things about New York is that you can present music to incongruous audiences. They’ll still be receptive and enthusiastic. Have you had opportunities to perform music of this hybridized to more traditional audiences, in Iraq and beyond?

AE: Yes, I’d say the most pronounced was when I had my “Rivers of Sound” Orchestra in Abu Dhabi. It was NYU Abu Dhabi, so the audience was mixed between NYU international students, American and British professors and ex-patriots, and then a whole section of Emiratis, Arabs who came to see an ‘Iraqi’ performance happening. I don’t know exactly what they expected, but I could see them very clearly from stage, outdoors in rows of seats. They were really into it. My interpretation in the moment was that they were grasping elements of Maqam and traditional Iraqi poetry, but hearing this whole context surrounding it, with drum set, bass, saxophone, vibraphone, a big wild swirl of sound. If you were to remove all of these other elements, I’d be singing the Maqam in the exact same way I’d be singing it in a coffeehouse in Baghdad with traditional instruments. So, the listener, especially the Arab listener, can pick up on that sound, and after that concert there was a lot of enthusiasm.

Similarly, we played in Oman at the Royal Opera House, and people talked to me afterwards. One approached me with a friend, and they said “Wow, this is really different. Do we like it?” [Laughs] They had to ask themselves, and that’s really interesting to me. Maybe someone won’t like it, and that’s fine too. Maybe it’s too chaotic or unfamiliar, but that questioning about your preferences is vital. Rather than “This is a packaged piece, we’re going to do it like we’ve done it many times before,” we’re presenting something new for people to consider.

TJG: Playing this music on trumpet takes a lot of technical and stylistic innovation, in terms of being able to play microtones, certain kinds of ornaments, and so on. Have other trumpeters taken an interest in your approach to the instrument?

AE: I can’t say exactly, but there are a few other Arabic trumpeters out there, playing microtones. You may have heard of Ibrahim Maalouf, he’s very famous in France. Musically and aesthetically, he’s doing something very different from me, with a different purpose and goals, but he’s definitely got his own style of playing the trumpet. He came at it independently through his father, Nassim. Then there’s my hero, my musical mentor, a guy named Sami Elbably. He was playing really pure Egyptian music, real classic and pop music from his era. From the 60s, 70s, 80s, all the way through the early 2000s.

TJG: How did Sami Elbably influence you?

AE: The first time I heard Arabic trumpet, I never imagined it might be possible. I was learning the trumpet, and thought I’d never be able to play traditional Arabic music. I didn’t know it was possible to play quarter tones. Then I heard a recording of Sami Elbably, and he was doing all of the ornamentations and microtones, making the instrument sound like a traditional Arabic instrument. The sound really captivated me. I went to Egypt in 1999 and I met him. I sat with him, he played for me, he invited me to his home for dinner, I watched a rehearsal with him, and I spent a good part of a day with him. We met once more after that, but sadly, he died about a year and a half later after a car accident. I had been planning to study with him and spend more time around him. He was sixty-five, but still had a lot of music in him. He was rarely featured on his own, he was usually accompanying singers. But there are a couple of albums where he’s playing extended improvisations. Never mind that it’s Arabic trumpet: The music itself, the sensibility, the emotion, it’s so beautiful.

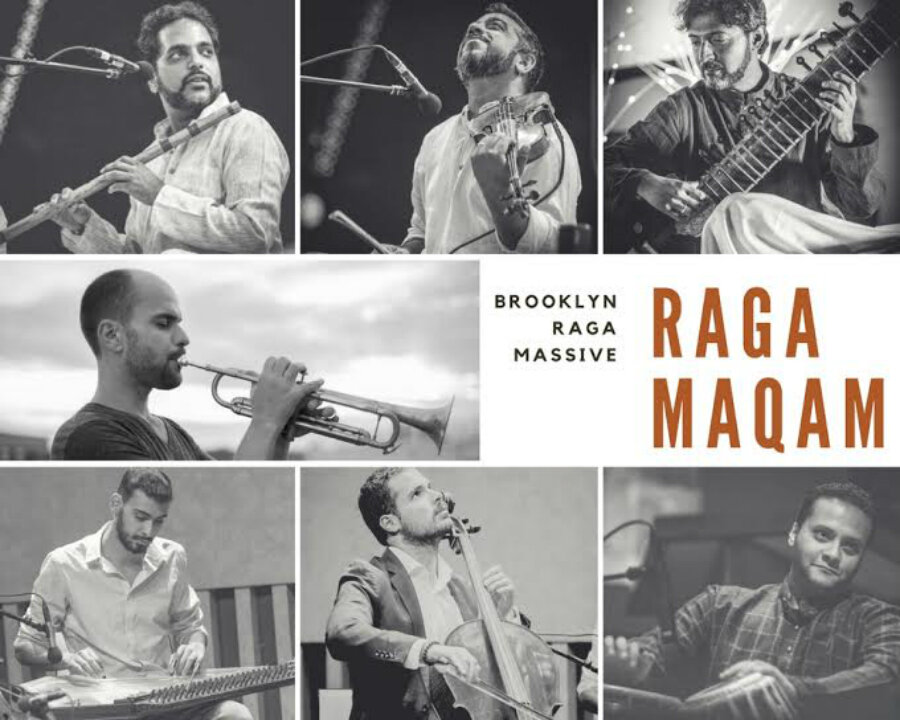

Brooklyn Raga Massive presents Raga Maqam with Amir ElSaffar at The Jazz Gallery on Friday, April 20, and Saturday, April 21, 2018. The group features Mr. ElSaffar on trumpet, Arun Ramamurthy on violin, Firas Zreik on kanun, Abhik Mukherjee on sitar, Naseem Alatrash on cello, Jay Gandhi on bansuri, and Shiva Ghoshal on tabla. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. each night. $25 general admission ($10 for members), $35 reserved cabaret seating ($20 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.